What is an emotion anyway?

Modern psychologists have offered several theories to explain what exactly qualifies as an emotion. While we all have them it can be difficult to define what an emotion is without having to use a placeholder, like “feeling” to describe the emotion.

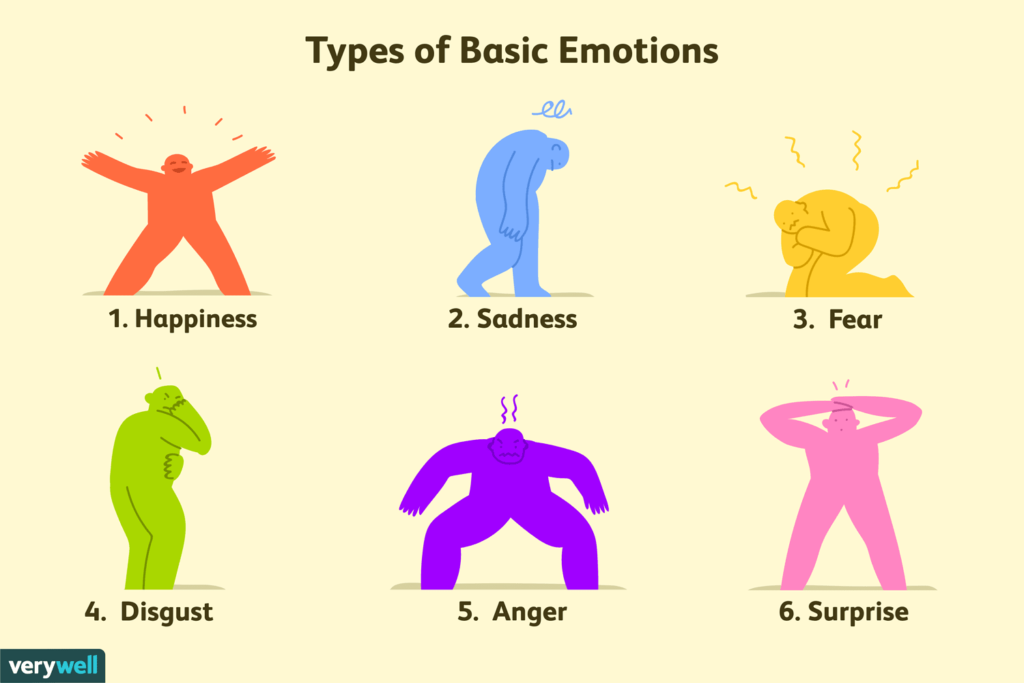

A general modern consensus however is that emotions are some kind of physical reaction to a stimulus. That consensus is fairly broad and there is further nuance between individual theories. There is however also agreement about the six basic universal human emotions. They are identified as fear, anger, happiness, disgust, surprise, and sadness. Most would agree however that our emotional experiences can range beyond these six as a result of various combinations of these together.

While this is helpful, we can look to a medieval thinker, who using philosophy as a foundation assessed what were referred to then as “appetites” and “passions” to gain a more robust understanding of emotions. While the medieval concepts of appetites and passions aren’t 1:1 correlation with modern conceptions of emotions, there is plenty that Thomas Aquinas writes about to give a clear systematic analysis of the internal life of the person. In this article I want to offer 3 helpful pieces of information from Thomas’ philosophy to help you understand emotions more clearly.

#1: Emotions have a hierarchy.

One of the most profound ideas that Thomas gives us is that love is the primary emotion and without which we could have no other emotion. It is primary because we all fundamentally are assessing things in our lives as worthy of love, or not. We can only hate some if we perceive that the thing, we hate is somehow ruining or impeding on what we first loved. Similarly, we have to first experience a desire before we can experience an emotion like hope. But for Thomas, love is first, both in order and in importance. Everything follows from that.

#2: Categories of emotions

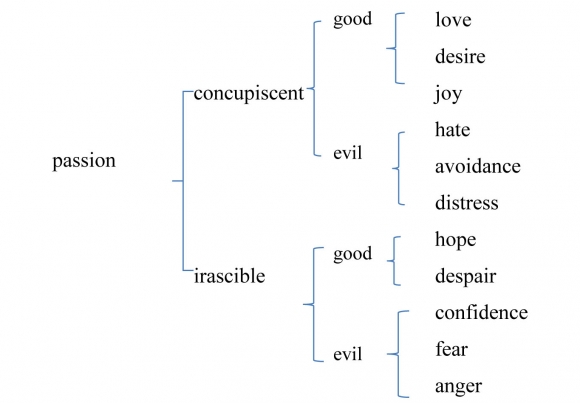

While Thomas starts with Love, he breaks emotions into 2 groups, based on his understanding of Aristotle who observed that we want both things that are easy at times, and other times we want things that are hard/difficult to get. Within these two categories he has further distinctions based on whether thing is desirable or undesirable, and finally whether it is present or absent from us. In total he lists 11 emotions, 6 under the “easy” grouping and 5 for the “difficult” group.

For the easily obtained things he notes that we have love (which is not the desire nor the delight in the thing) but is the first principle to move us to desire the thing, and without which no other emotion would occur. Love is what orients us towards the thing perceived through our senses as good. The emotion that is contra-orientated to love then is hate perceived through our senses as evil. In this case we may hate something only after we have loved something else first. We may hate disease (evil) because we first love our bodies (good).

When we love an object but have not possessed it yet, we experience desire naturally, but if the object is hated and not possessed yet then we experience an aversion to that thing in order to avoid the evil.

Finally, if the object is easy to obtain, perceived to be good, and we actually possess it, then we experience joy, for we got what we wanted. When an object is easy to obtain, hated, and we possess it/experience it then we experience sorrow or sadness at experiencing the present evil.

So, our couplets are love/hate, desire/aversion, joy/sadness.

For the second category of emotions, pertaining to difficult things to obtain, Thomas names 5 emotions. Similar to the list up above he gives further clarification to the difficult thing, in that it is either loved or hated, and present or absent. When we desire difficult things that are not present but good, we experience hope. Hope is built on desire, and allows us to persevere for the good thing despite the trails we may face. If, however it is not only difficult and good but judged to be impossible to obtain, then we fall into despair. If we do actually obtain the good, at the time of getting it, it is no longer difficult, so we then revert back to joy.

When we think about evil things that are difficult to overcome, I’m sure there are plenty of things that may come to mind in our world today. Courage arises when we judge something as hard, evil, not present, but we should engage it. As John Wayne said, “Courage is being scared to death, but saddling up anyway.” If the evil is not present and we try to avoid it we are experiencing the passion of fear, the active avoidance of an evil. Finally, when we face a present evil which we have hope that we can overcome, we are roused by anger in order to combat the evil present.

Our couplets then, for things difficult to attain are hope/despair, courage/fear, and anger.

For a helpful graph see below. (Note: A few of the terms I use are different than the graph below)

#3: Your judgements are key.

Our emotions are rooted not only in the external stimuli, but result from our judgment about the stimuli. Here, Thomas is in lock-step with an observation made from the ancient Stoic, Epictetus who stated, “Man is troubled not by events, but by the meaning he gives them”. This view point is also shared by modern cognitive behavioral therapy which helps people distinguish, “A”, the activating event, from “B”, the belief about that event, to “C” the consequences of that belief. We run away from the Tiger in fear because we judge the presence of the tiger to be a threat to our lives. That judgement may prove to be true or false.

There are many ways this kind of conceptual breakdown can be helpful. Often doing the hard work of identifying and naming our emotions is key first step towards addressing the issues and moving forward. Like the modern concept of emotions, Thomas’ framework allows for combinations of these various classifications of emotions. Anxiety for instance, may be a combination of hope and despair. Or one may experience first courage then anger in order to address an injustice in the world.

Using his framework, we can ask ourselves, is what I’m feeling dealing with something relatively easy or difficult? Is the feeling related to something that is lovable (that I may or may not have) or something evil that I wish to avoid? And finally, is the thing something that is present to me, or something that is absent but could be present in the future? By using this series of questions, we can more accurately identify what you are experiencing and why? Why do you judge that thing to be an evil to avoid or a good to pursue? From there we can evaluate if our judgement is accurate or not, and then formulate a plan on how to avoid the evil or work to obtain the good in question.